Microsoft’s Lili Cheng on making bots more human

For more than 20 years, Lili Cheng has been shaping the way we chat.

First with Comic Chat, a graphical IRC feature built into Internet Explorer in the mid ’90s and now as Microsoft’s Vice President of Artificial Intelligence and Research, where she oversees the company’s Bot Framework and Cognitive Services.

On the heels of launching Intercom’s newest feature, Custom Bots, I hosted Lili on our podcast. We talked about how bots and humans can work better together, when and how to give your chatbot a personality, and how the earliest chat experiences still inform what we build today. If you enjoy the conversation, check out more episodes of our podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes, stream on Spotify or grab the RSS feed in your player of choice.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation. Short on time? Here are four key takeaways:

- In 1995 – long before social networking and even the ubiquity of cell phones – Lili worked on an IRC system that was ahead of its time. The constant between that and her work on chatbots today? Putting people at the center of the experience.

- A common misconception is that AI will replace human employees. In reality, the two should work hand in hand to provide superior answers to user queries, with bots responding to repetitive tasks and simple answers while employees are free to tackle more complex problems that require a bit more human finesse.

- With the rise of AI, we’re seeing personality-driven bots like Cortana, Siri and Alexa. But not every bot requires its own persona: you don’t want a social chatbot personality in a business setting, but you also don’t want a stodgy business persona in a social environment. It’s important to consider the use case.

- The future of AI is bright. In the short term, Lili and her team aim to make the computing experience by designing more fluid ways for people to talk and type. Farther out, they’re focused making their tools open and deploying their speech and vision experts to help people better understand what AI can do for them.

Adam Risman: Lili, welcome to Inside Intercom. Can you give us a quick feel for your current role at Microsoft and the types of products and initiatives you touch that our listeners might be familiar with?

Lili Cheng: Thank you. It’s great to be here. I am the Corporate Vice President at Microsoft in the AI and Research Division, and I focus on all of our conversational AI. That includes things like our bot software, bot framework, the Azure Bot Service, language understanding and more.

Adam: AI is one of the most debated and misunderstood phrases that gets batted around right now, particularly in media. In the context of your work, what does AI mean exactly?

Lili: My work focuses on AI tools, so that’s speech, language, vision, knowledge, search. They’re tools that help developers or just anyone out there incorporate these services into their own apps.

Adam: Going back a ways in your career, I believe you were actually originally an architect. How does an architect get into computational design?

The origins of chat

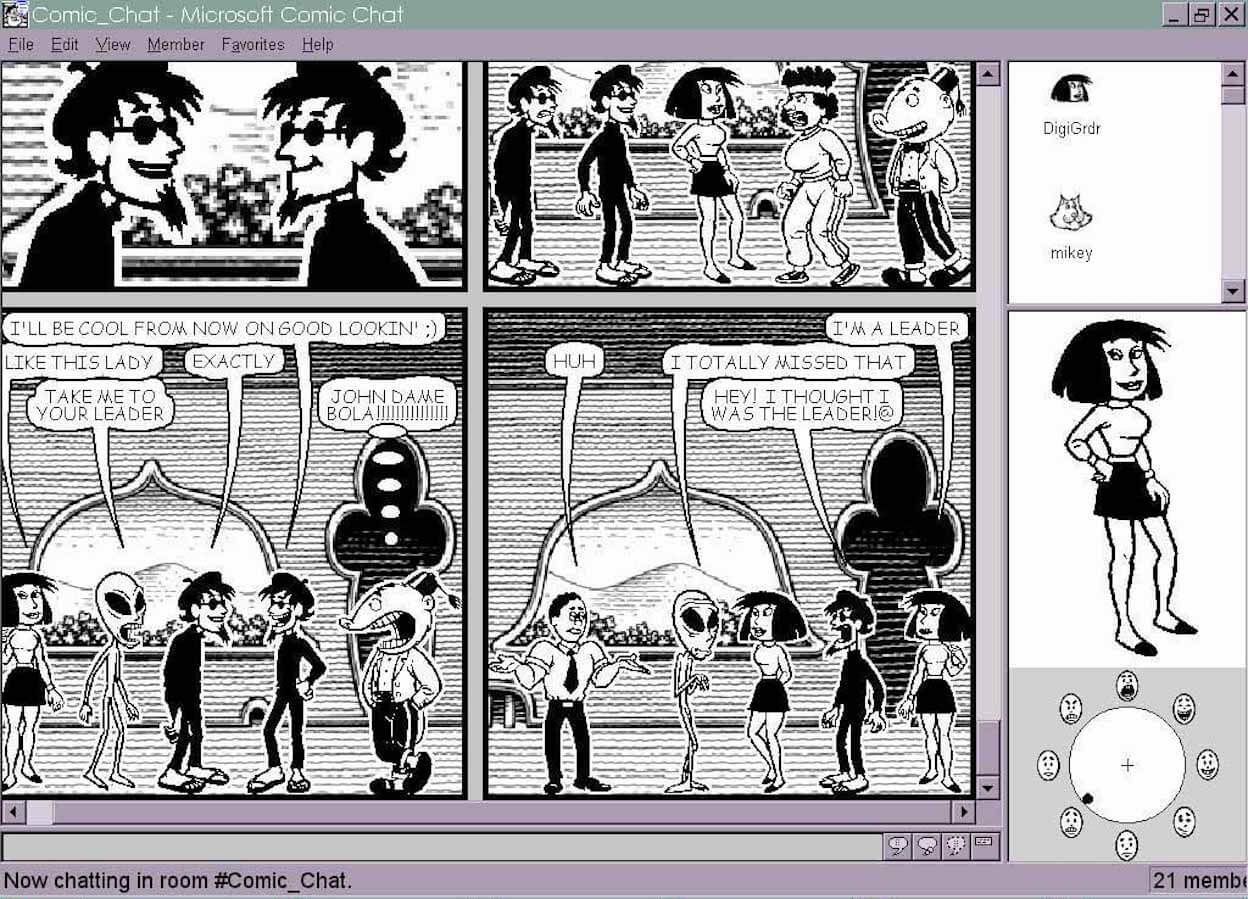

Adam: One of the most interesting early applications of a conversation project in your time at Microsoft was Comic Chat, the graphic IRC from way back in the mid ’90s. Can you explain for our listeners a little bit about what that was?

Lili: Back in ’95, we were interested in the internet and how people converse. At that time, the most common way people would converse or chat online was through IRC, or Internet Relay Chat. The term bot actually comes from that era. One of the things we were interested in doing with IRC is thinking about how people create their own topics and how people communicate in groups. We were interested in thinking about how people could be more expressive.

We actually had two products. One was Comic Chat, which basically made your conversation history a comic book or a visual history of what you said. So if you said hi, it would make you wave. We worked with an amazing local comic artist here in Seattle named Jim Woodring to create all of the artwork, which we componentized and we basically made a graphical way for you to converse with your friends.

Adam: Was that a passion project at the time, or what was the main goal that your team was trying to achieve?

Lili: Well, what’s kind of funny is back then – I don’t remember what version of Internet Explorer we were working on, but that was actually the default. IE had a chat client inside of it, and Comic Chat was the default UI you got with Internet Explorer. I’m not sure why we did that, exactly. I think it was because we were exploring the internet and how people converse, and we’ve always been interested in how to make conversation and dialogue more expressive. What’s been cool for me is that 20-some years later we’re bringing back bots and focusing the user experience back on conversation. So much has changed over the years, obviously. Things like social networking didn’t really exist back then or cell phones even, and so much of what we do today. We’ve always believed in putting people at the center of the experience and the power of conversation.

Adam: Absolutely. Conversation is the original UI, so to speak. It’s the first way that we all interacted. The problem you’re facing is still something we’re trying to continue to iterate on and solve today. What were some of those early design principles from that project that still hold true in your work today?

Lili: Today, you actually interact with your phone and other people in chat or text messaging and email so much more of your life than we could have ever dreamed. Today people probablyspend four or five hours on their phones alone, much less their PCs. We always believed we should do more with what you input, with what you say, with what you type, and just be smarter about that. I think that underlies the design of the computer from the very beginning. If you go all the way back to the command line, it was a dialogue that you had with your system. It’s always been a dream.

We’ve always believed in putting people at the center of the experience.

With Comic Chat, we tried to say that if you said “wave” or “hello” or “hi” or “goodbye” or you said commands, the system could show you being friendlier. Comic Chat was a fun social chat app. One of the dreams we have is that you can do less. The system just works on your behalf and follows more the principles and the ways people are familiar with just in the way they converse. So if I’m meeting you for the first time, the system can just help me, rather than me have to drive it as much as you have to do today.

Chatbots return to their roots

Adam: It’s interesting that you mentioned the command line there, because it’s what all this stems from, thinking back just a couple years ago when conversational commerce became the big buzzword around Twitter and everything about all these applications. Still, a lot of those early interactions were a lot of if/then statements. In the last couple of years, it’s snowballed from there. What are the most exciting applications of this stuff that you’re seeing right now?

Lili: We’ve been interested in seeing how companies want to use these tools to help them do business. Our company thrives when other companies succeed, so some of Microsoft’s business is based on you’re making your company run better. I’ve been surprised and interested in how companies are using AI in general.

As you said earlier, AI can be a very misunderstood term. It’s not magic. Typically, there’s actually technology under there working that somebody built. People can misunderstand what AI can do for them. We’re interested in talking to companies, figuring out their core challenges, and then learning what kind of apps and things they want for their customers inside their companies. Bots, not surprisingly, have been something companies have been interested in doing, mostly because there are two scenarios we see companies building. The first one is that they want to talk to their customers, but it turns out, there aren’t a lot of times a customer is dying to talk to a company. Why is that? Why do customers not want to talk to companies?

Online, we haven’t made that a great experience in the past. Historically, companies spend a lot of time thinking about the design of their shop or their store or their physical presence, and they haven’t thought as much about beginning with the online experience. Today, the first time you experience most companies is in your search results: you click on their website, and you might interact with their products online, versus going into the store. So that communication you have with your customer, beginning online, going into the store, building over time, just needs to be better. So we see a lot of companies wanting to do that.

Then, the other scenario we see companies being interested in is just making work inside their company easier and more effective and being more conversational. Of course, we have some fun social experiences as well.

Adam: So you’re saying that consumers should be able to get in contact easier, quicker, faster with the businesses that they’re patrons of through ubiquitous channels, correct? Customers used to be able to go and talk to someone right away, face-to-face. Then the web comes along, and all of a sudden they have to fill out a form to get in touch with someone. It doesn’t have that immediacy, and it really kills the relationship.

Lili: Yeah. Customer support is a great scenario. Typically, something has to have gone pretty wrong if you want to pick up the phone and call a company and get help with something. That’s probably not the best business strategy for dealing with your most devoted customers.

Designing for synergy, not replacement

Adam: Looking at AI in general, I think there’s a conception that this technology is supposed to replace something. But perhaps technology and people are supposed to work hand in hand where a single option maybe isn’t the most efficient answer (for example, when a customer is doing some light investigation into a product and there are a lot of quick, repetitive answers that aren’t the best use of a human employee’s time). How do you see humans and bots coexisting?

When you’re building a conversational experience, don’t let your lead technology limit what a user does.

Lili: I see them as one in the same system. One of the most common things we have people add to a bot is what we call “person in the loop,” which means that when you build an AI system, especially for a company, often you’re trying to do something specific for your company. Unlike a company like Microsoft or Amazon or Google, you might not have tons and tons of data around your customers’ interactions, because you’re trying to just sell an insurance policy or get somebody help with their medical process.

It’s important when you’re building a conversational experience to not have your lead technology limit what a user does. What I mean by that is if you launch an AI service and it can only do one thing and it doesn’t do anything else at all, you might not learn what your customers really want. You might be teaching your customers that you only do one limited thing. Typically, people will ask for a wide variety of things. We encourage companies to assess what their systems can do – or if it can’t do something, hand it off to a person who can make sure that you don’t lose a customer in that experience.

People are great at learning new things, ambiguous things, and complex problems. And the idea is that it’s important to pair bots that can do repetitive tasks and solve a lot of simple problems people have with employees and workers who can do more complex and interesting things.

Adam: Thinking back to a few years ago, chatbots got a lot of criticism – maybe they fell flat, or maybe they were too general purpose. Have you seen these applications become more people-focused?

Lili: It’s interesting. If you go all the way back to 1995, one of the things we learned was that we were just early. Consumers weren’t used to chatting. They barely had email accounts, and the internet was pretty slow back then. So the people who were chatting online were a small segment of the total number of people communicating. That’s been one of the biggest changes. Today, pretty much anyone who has a phone gets text messages. People are used to feeds, email, and instant messaging. You can’t imagine life without these tools today. Although they’re popular, ppeople aren’t necessarily used to communicating with businesses in these tools.

But sometimes there’s an experience that changes your mind, where you say, “Wow, that was just awesome. That totally saved me time, or that experience was so much better.” That change encouraged you to try others and use them more and more. I think you’re going to see that a lot with conversational experiences.

When a bot should – and shouldn’t – have a personality

Adam: Microsoft has been doing a lot of work on the idea of personality within bots. In fact, your team recently announced the Project Personality Chat, which enhances a bot’s ability to handle small talk with a chosen personality. Should all bots have a personality, or does it depend on the context?

Lili: It definitely depends on the context. For me, a bot, in a sense, is just a conversational app. I’ll give you an example of one that doesn’t have that much personality: one of our most popular bots is just a translator bot. In Skype, you can talk to the translator bot, and you can translate in real time from one language to another. It’s just a service, and it was a way we could embed that functionality right in your conversation. So is it a bot? Is it just an app? Is it a service? The line kind of blurs, but you might not want your translator to have its own character, because it might disrupt. You just want it to work, just translate what’s happening, and kind of be in the background. Most companies have a brand, and they have a point of view in how you interact with them, so the voice should be in line with the company’s brand.

A great example is a bot that we worked on with Progressive. Progressive has a persona, Flo, who’s a character you interact with. And their bot has Flo’s character. It matches their brand and their tone and is consistent with what a Progressive insurance customer would expect. That character could also change a bit depending on if it’s embedded in Facebook or embedded in a teenage audience or an older audience. It could shift, just like a person does when you interact with someone.

I think personality is key. Obviously, you don’t want a very social chatbot personality in a business setting. It would just be inappropriate. You also don’t want a stodgy business persona in a social environment. Probably, the example where we’ve pushed this the most is with a very popular chatbot we have in China called Xiaoice, where we see that technology powering many other characters in Japan and China like Pokémon and a bunch of the other Asian personas.

Adam: That’s an interesting example, because it brings up the topic of localization, which is one of the more complicated aspects of this. If you are designing a personality, how does that translate to a different market, where different euphemisms are interpreted differently?

Lili: The way we thought about it at Microsoft is that technically there are two ways, and then socially there are a few ways. Some people want to fully author the experience in different languages, especially their primary languages that their customers are engaging with. In that case, you want to handcraft it a little bit more. You want to make sure it matches the slang and terms and dialogue that are customized to your application. In other cases, maybe you don’t want to do that much. You might not have the resources to invest that much work. In those cases, we allow people to use machine translation, like the real-time translator I talked about before. Then, one of the things we’re looking at is being able to customize it by giving it your own custom dictionary in a particular language. We’re seeing that people kind of want both, depending on how involved they want their experience to be.

Adam: When it comes to actually designing the personality for a brand’s bot, are there certain questions you ask? Or is it really as simple as: “We have our brand, voice, and tone guidelines – now, we just need to design that into a conversational experience?”

Lili: I think starting with that is key. Most companies actually think about that from the beginning. They’ve already designed a website. They already have an app. They have a look and feel. Even on their website, they have some sort of text, and they want to own how the character interacts with the customers. That’s pretty intuitive if you work for a company, but then how to make it real and believable is something that we help companies with. What are all the things you might want help authoring so you don’t have to start from scratch? What elements can we package up and provide a company so they don’t have to author all kinds of things about time or just general Internet knowledge? As far as dialogue, that’s one of the most fun parts. It’s interesting to ask: What are your goals? Is your goal to quickly serve your customer and provide them as quickly as possible with the information that you want? Or are you an entertainment site, where you want your user to stick around and talk a lot and have an engaged experience?

Dealing with conversational latency

Adam: It absolutely comes back to problem definition there. I imagine that when you encounter these types of experiences in your personal life, you’re someone who evaluates them a little differently than the average consumer, due to the nature of your work. Are there any common pitfalls or best practices you wish the average listener knew better than to do?

Lili: There are so many. One thing that’s interesting is the latency of conversation. When you text a friend, sometimes you have these gaps where you’ve said one thing and then a second, but they’re responding to the first thing. You kind of have these conversational glitches, and you have to clarify by saying, “No, no. I was talking about the first thing.” Or you maybe use a lot of emojis to signal that you were kidding.

It’s important to give the consumer ways to correct the conversation.

Humans talking to each other via text is different than talking in voice, because you just don’t have all the social cues. One of the things we think about a lot is that there is latency when you chat with a chat box, sometimes because the system is actually looking up an answer for you and getting back to you. Sometimes it responds so quickly that it feels inhuman and unnatural to get an answer back so quickly. You think, “How did you type that fast?” It just doesn’t match the cadence of talking with a person through text. That’s one of the things we help people with. How do you converse with the kind of latency that feels proper? Then, how do you design an experience in case you have a lot of latency coming back – making sure you let people know you’re working on an answer?

Then, if you do have those glitches I mentioned, maybe you’re answering the first thing somebody said but they wanted you to answer the second thing. It’s important to give the consumer ways to correct the conversation. Otherwise, it can get kind of frustrating, just like it can get frustrating with text messaging your friend.

Adam: Absolutely. Even little things, like the signal that someone is typing – that they’re still there.

Lili: Right: the “dot, dot, dot.”

Adam: That helps to humanize the experience. Have you come across anything new in the space that has you particularly excited?

Lili: We’re intrigued by systems that can keep your interest for longer and that can be more general-purpose. One of the things we see is when you converse with someone, you’re dropping into one topic and pulling out and then dropping into another. If you think of designing apps, we might call that “deep linking.” In this podcast, if I change topic and suddenly say “Xiaoice” again, you’re going to know to pull back into that topic. It’s interesting to me if software can follow the mind of a person and be able to shift more dynamically based on what you’re talking about and bring you that information right away.

That’s one of the biggest advantages of these types of systems, and it means that you do need to build them a little differently. You need to make sure you componentize your app more and so you can make those transitions easily and solve errors. I think if we can respond more quickly to what someone says and bring them the information faster, it makes it interesting. It’s just going to completely change the way we build software. It’s super exciting to go all the way back to the command line, rethink it, and experience it in a simple way that’s completely centered on the way people converse.

Returning to first principles

Adam: It sounds like your thought process is looking back at the first principles of conversation and applying them into a modern framework, which is a really exciting problem to solve. Your team is definitely at the forefront of it. When it comes to Microsoft’s bot framework specifically, what would you say is your special sauce?

Lili: We have a very comprehensive system. Because we work with so many different companies, we’ve tried to make sure that the experience is customizable for the kind of bot that you’re trying to make. A lot of your questions reference that. Almost all of the companies and customers that we work with require that their data be private and comply with all of their GDPR and other regulations. It just means that you have to build your AI in a different way, where you’re not inspecting people’s data at all. That’s been big for us, and we’ve thought about how to build AI that doesn’t need that. But if you do want to leverage some pieces that are shared, you can leverage data and services. Designing for business scenarios first is great, because I think it will help all the consumer scenarios, as well, with the privacy and data compliance and issues that people are so concerned with today.

Customization is the other thing that’s been cool. A lot of companies want to experiment first in Brazil or Italy or different countries, so it’s critical to think about how we can make things work in a particular region and locale for that audience. We need to let companies incorporate not just Microsoft’s AI services but their own custom AI services or AI services from other companies, their own customer database, or their own software. It’s a conversational app. We want to give you all the power that you have in customizing an app, while bringing that to dialogue and conversation. We’ve focused on solving some of these tricky problems for companies like Vodafone, Telefónica, and so many others who are trying to do more sophisticated things and integrate with a lot of their existing services. We want to make that easy for them and give them the power to integrate all the tooling they want.

So, that’s been something that our customers love. They want to own their AI future, and they don’t seem to want to take a bet just on one company. They want to be able to combine and mix and match all kinds of services, so it’s critical to make sure we’re really open and that we support many companies and many AI techniques at this early stage.

Adam: Looking forward, what are you most excited about where this type of technology is headed? What type of change would you be excited to look back at and say, “Our team helped make this happen”?

Language understanding is at the core of being human.

Lili: If you think back to the early days when we worked on Comic Chat, I don’t think we would have imagined we would just be here 20 years later. Language is really hard. Language understanding is at the core of being human. Even humans have problems with language understanding, sometimes. I guess the aspirational thing is to make it easier for people to do more with what people say and type so that the computing experience is easier. That’s kind of the dream.

Shorter term, we’re committed to making our tools open. Four or five years ago, from Microsoft Research, we launched the cognitive services that are now embedded in Azure, our cloud. We were the first company to do that, because we had Microsoft Research for 25 years. We’re so lucky and fortunate to have the world’s speech experts and language experts and vision experts, and most people don’t have this research organization in their back pocket. We thought if we could make these services available to anyone, we could actually have a lot more people who have real problems or fun ideas come alive with vision and speech and language and knowledge. I never would have dreamed back then, when we debuted the cognitive services, that AI would be everywhere.

When you go to any computer science department or any conversation, AI is on the forefront of people’s minds. That’s super cool, and now we need to make that even clearer for people: What does AI mean for you and your company or your education? How does it impact what you can do? My team and I are focusing on beginning with language. AI can be there in the background, providing machine learning over data – or speech and vision and other areas people at Microsoft are working on.

Adam: These are really exciting prospects, and you’ve mentioned some big questions. But they’re definitely questions we should all be asking of ourselves so we can capitalize on this technology to build relationships with our customers and users. Thank you so much for joining us today, Lili. It’s been awesome to have you on the program. Quickly, where can our listeners go just to keep up with the latest that’s going on with you and your team?

Lili: Botframework.com is a great place to start. Thanks so much.